The Controversial Third Tone in Chinese

A brief discussion about the different ways the third tone in Chinese is taught as well as third tone sandhi or tone changes.

I recognise that one of the most annoying struggles when I began to study Chinese was the third tone: ǎ ě ǐ ǒ ǔ. Needless to say, I am not an expert in phonetics, but I wanted to bring the knowledge I had found together and keep it in a post for me to read when I need reassurance of “yes, I am saying the tone as it should be” and to help any reader interested in Chinese but struggling with the third tone.

During my first Chinese lessons, I understood that the third tone goes down slightly and then goes up, just like the little “v” that marks the accent (notice the “v” on top of ǎ, for instance). However, as I gained a bit of speed at pronouncing basic words like 老师 lǎo shī, I began to struggle with making sure that the “v” pronunciation was kept; when I head the teacher talk, I felt as if my way of intoning was not the same as theirs (and I am not talking about experience with the language, I am talking about feeling like “there is some clue I must be missing here”). Moreover, while I was slowly introduced to some basic rules that establish changes in tones when certain conditions are met, I was still not quite happy with my understanding of the third tone; therefore, I did something I often do while learning Chinese: read what other professionals, studies and research, and experienced speakers had to say (oh yeah, research time 😎).

Also, I am writing this post 4 years after my discovery. Why? Well, because after I began to address my issues with pronouncing certain phonems while I was in China (or, put into other words, after noticing that Chinese people did not understand me at all when I was speaking Chinese), I thought that it would be fun to record some of the findings I believe were key to improving my Chinese!

A dipping tone, or a low tone disguised in tradition?

First of all, just to be clear, the five basic tones in Mandarin are:

- first: “ā”

- second: “á”

- third: “ǎ”

- fourth: “à”

- fifth / neutral (I like referring to it as “fifth” tone): “a”

I did some research about tones in Chinese, read forums, and watched videos to get around the idea of how to correctly intone syllables. However, most of these resources explained the third tone in isolation as a dip-then-up sound, like intoning down and up (“v”), and then hopped onto words and examples where such dipping was not noticeable (hey, at least for me, okay? (⌐■_■)), leaving me even more confused.

Therefore, I began to be off my rocker. (╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻

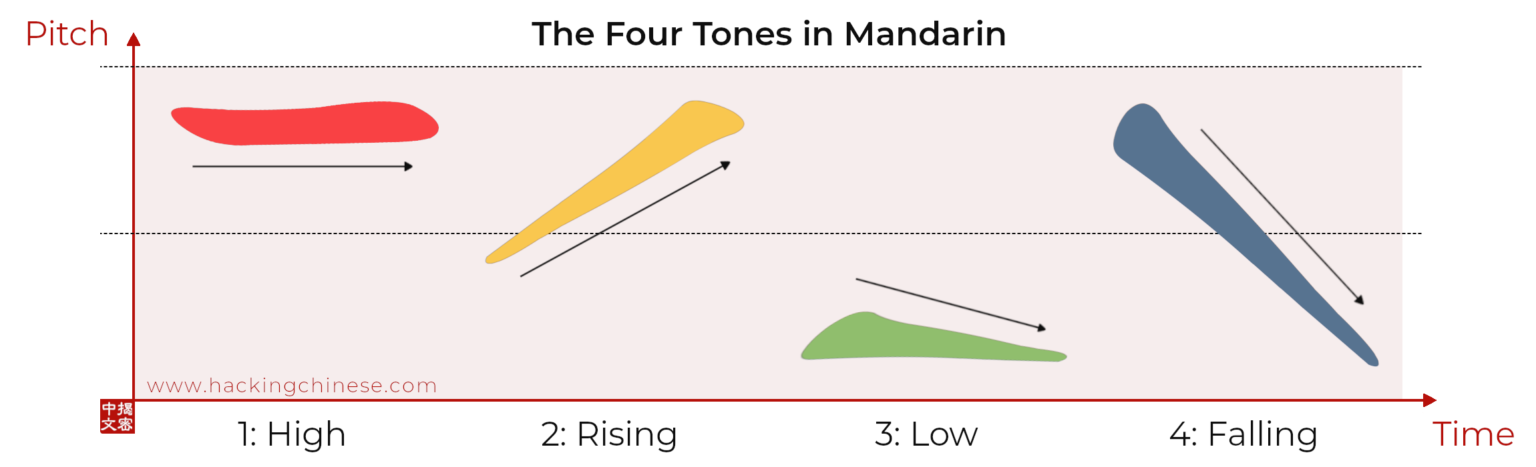

That was until, while browsing for diagrams of the tones in Mandarin, I stumbled upon this picture:

This diagram shows the third tone as a low tone. Low tone. Low tone! If you have been learning Chinese for a while now, and you have never heard of the third tone being a “low” tone, this might come as a shocker to you, too, dear reader. At least, in my case, I was utterly astounded, because my way of pronouncing it was mostly always (and erroneously) “dip-then-rise” (remember, I was a beginner around that time).

Third tone sandhi, or 变调 biàn diào. Quite literally: “tone change”

I searched for the source of the image and found the blog Hacking Chinese, which had a post called “Learning the third tone in Mandarin Chinese” (click for more info), by Olle Linge. There, the author not only talks about sandhi (those rules I mentioned at the beginning), but also introduces the discussion of teaching the third tone as a dipping tone vs a low tone, favouring the latter. What I liked about his arguments pro-third-tone-as-low-tone was that he balances frequency with the tone change rules. I’ll quote Olle’s comparisons directly because I think they are perfectly clear by themselves:

Teaching the third tone as a low tone:

- No rule required in a large majority of cases

- When two appear in a row, change the first to a rising tone

- When in isolation, add a rise to the end

Teaching the third tone as a dipping tone:

- In a large majority of cases, change to a low tone

- When two appear in a row, change the first to a rising tone

- No rule required in isolation (quite rare in connected speech)

Now, this is not saying that the third tone is exclusively a dipping “v” tone, nor exclusively a low tone; after all, there has been plenty of analysis of phonetics in Mandarin and there are cases where the third tone follows a “downwards” and “low” tone and other cases where it follows a more “v” trend. Therefore, this analysis by Olle aims to shed some light on how to address teaching the correct intonation of this tone pedagogically, answering the question: “What ruleset is easier to apply?”. Let’s consider some examples (I’ll be referring to the third tone as “v” or “dip-then-rise” interchangeably).

If the third tone is considered mostly “low”:

| Case | Word | Meaning | Pattern | What to do with the third tone(s) | Pronunciation | Change? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 老师 | Teacher | 3+1 | Say as low tone | lǎo shī –> lǎo shī | No |

| 2 | 可能 | Maybe | 3+2 | Say as low tone | kě néng –> kě néng | No |

| 3 | 你好 | Hi | 3+3 | Change first to rising tone (2), say second as “dip-then-rise” | nǐ hǎo –> ní hǎo | Yes |

| 4 | 小路 | Shortcut | 3+4 | Say as low tone | xiǎo lù –> xiǎo lù | No |

If the third tone is considered mostly “dip-then-rise” (“v”):

| Case | Word | Meaning | Pattern | What to do with the third tone(s) | Pronunciation | Change? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 老师 | Teacher | 3+1 | Change from “v” to a low tone | lǎo shī –> lǎo (low) shī | Yes |

| 2 | 可能 | Maybe | 3+2 | Change from “v” to a low tone | kě néng –> kě (low) néng | Yes |

| 3 | 你好 | Hi | 3+3 | Change first from “v” to rising tone (2), keep second as “v” | nǐ hǎo –> ní hǎo | Yes |

| 4 | 小路 | Shortcut | 3+4 | Change from “v” to a low tone | xiǎo lù –> xiǎo (low) lù | Yes |

As you can see, on the one hand, when the third tone is considered mostly a “low” tone, in 3/4 examples we keep the third tone as “low”. Then, in the 3rd case, the first third tone changes to a rising tone, and the second third tone changes from a “low” to a “dip-then-rise”. On the other hand, when the third tone is considered mostly a “dip-then-rise” tone, in 4/4 examples there is some kind of change. Cases 1, 2, and 4 change from the “dip-then-rise” to a “low”; case 3, just like in the table for “mostly low”, changes the first third tone to a rising tone, but the second third tone remains as a “dip-then-rise” due to our assumption.

Consequently, what is easier to memorise? The ruleset that causes less changes, or the one that causes the most changes and that can, therefore, maybe slow down fluency?

The more examples I used to check the ease of application for each ruleset, the more comfortable I felt with the “low tone” approach one. Before this discovery, I had been struggling making inflexions when appropriate, and thus my speech had not been as clear as it is now while talking (hey, it is not perfect, but I noticed some clear improvement and more mental agility), and it is easier for me to apply the “low” ruleset over the “dip-then-rise” one.

An Updated Ruleset for the Third Tone

Finally, just as my two cents to contribute to the cause, I would like to update the sandhi for the “low” third tone to be a bit more specific:

Teaching the third tone as a low tone:

- No rule required if next tone is 1st, 2nd, or 4th.

- If two appear in a row, change the first to a rising tone (2nd).

- When in isolation or at the end of a sentence, make it a “dip-then-rise” (i.e.: add a rise after the low). Note: fast speech might keep it as “low”.

I think this way it is a bit more comprehensive and clear, although the best thing to do is to read the full article! That’s what cool people do, anyways 😎.

Final Remarks

If you would like to read more about the third tone and different ways it is taught, you can also check the paper written by Olle Linge, 2011: “Teaching the third tone in Standard Chinese” (click here). I read his paper to get into detail about the ways the third tone is taught and how successful they might be. Quite interesting! I also liked discovering the different ways to “code” the pronounciation in levels, like “mà” as “ma51”.

Regards,

Saúl